External board evaluations – independent reviews of a board’s performance by an outside expert – have become an integral part of good corporate governance. Boards in the UK, USA, Canada, and across Europe are increasingly turning to external evaluations to gain objective insights into their effectiveness.

This report examines why external board evaluations matter, current data and trends in their use, best-practice methodologies, regulatory frameworks in key regions, common challenges, and emerging future trends.

It is designed for board professionals, directors, and advisors seeking actionable insights on leveraging external evaluations to strengthen board performance.

The Importance of External Board Evaluations

External evaluations bring an independent perspective that can uncover blind spots and foster candid feedback. While boards often perform annual self-assessments, an outside evaluator can probe sensitive issues and provide “priceless insights” that might be missed internally.

The UK government has noted that an external review is typically more detailed than an internal one, with greater focus on relationships and behaviours, allowing the board an opportunity for frank self-reflection that is difficult to achieve when the board evaluates itself . In practice, regular evaluations (internal and external) create a valuable feedback loop for continuous improvement.

An organization is only as effective as its board, and routine board evaluations help reinforce good governance, sharpen effectiveness, boost accountability, ensure strategic alignment, and identify areas for improvement . Many high-performing boards report that robust evaluations lead to improved processes, more transparent communication, enhanced trust among members, and better decision-making .

In short, external board evaluations add credibility and rigor to this process – they signal to investors, regulators, and stakeholders that the board takes governance seriously and is committed to learning and improvement.

Current Trends and Data on External Board Evaluations

United Kingdom

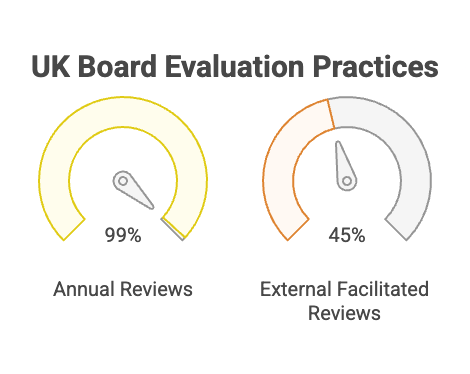

The UK has been a leader in adopting external board reviews. Almost all large UK companies conduct annual board evaluations, and a growing portion use external facilitators. The UK Corporate Governance Code recommends an external independent board evaluation at least every three years for FTSE 350 companies . Compliance is high – 99% of top UK companies report doing some form of annual board review, and 45% of boards had an externally facilitated review in the latest year (up from 41% the year prior).

In practice, many UK boards conduct internal self-assessments annually and bring in an outside evaluator every few years for a deeper dive. External evaluations have become the norm for major companies, and even smaller listed companies are encouraged to follow suit. (Notably, proposed updates to the UK Code in 2024 would remove exemptions so that all listed companies undertake an independent board review at least triennially.)

This trend reflects the UK market’s belief that periodic external insight is vital to keeping boards effective and aligned with best governance practices.

The better Way to evaluate boards

Gain valuable insights to strengthen your board and make better decisions.

United States

U.S. boards traditionally rely on annual self-evaluations, but external reviews are gradually gaining traction. Nearly 98% of S&P 500 boards conduct an annual performance evaluation of the board (as required for NYSE-listed companies), and about 47% also include some form of individual director peer evaluation in that process .

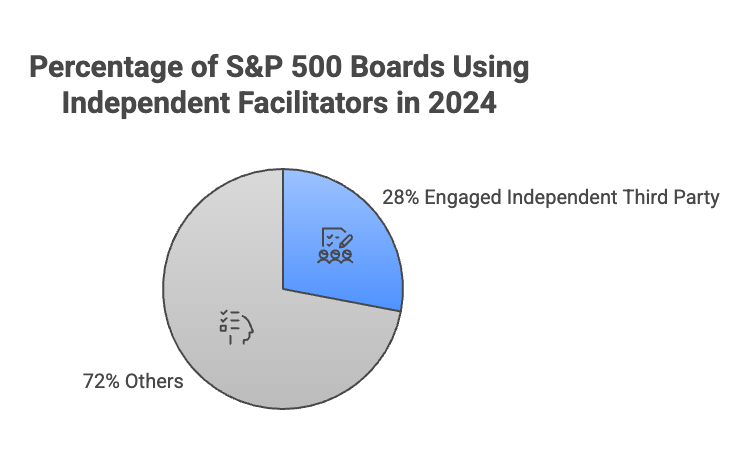

However, only a minority currently use outside facilitators – in 2024, about 28% of S&P 500 boards engaged an independent third party to assist with their evaluation, up from 25% the year before . This modest percentage likely understates usage since many boards bring in external reviewers only every 2–3 years (not annually) .

Surveys indicate U.S. boards are becoming more open to external evaluations as a way to avoid complacency. For example, board governance experts note a shift from viewing assessments as a “check-the-box” exercise to treating them as a tool for continuous improvement .

Leading companies and investors are driving this change – directors increasingly acknowledge that a skilled third-party facilitator can elicit more honest feedback and “tough conversations” than an internally led exercise.

The result is a slow but steady rise in external board evaluations among American companies, especially for addressing delicate issues like boardroom dynamics or underperforming directors.

Canada

In Canada, board evaluations are firmly entrenched as a governance best practice, and the use of external advisors is common for in-depth reviews. There are no statutory requirements in Canada for board evaluations, but regular evaluations are widely recognized as essential for good governance .

Virtually all large Canadian companies conduct annual board and committee assessments – in a recent survey of 100 top Canadian companies, every board disclosed evaluating its performance (covering the full board, each committee, and individual directors) .

These annual evaluations are typically overseen by the governance/nominating committee and board chair. Many Canadian boards supplement routine self-assessments with periodic external evaluations on a 2- or 3-year cycle to delve deeper into board effectiveness, culture, and governance processes . For instance, boards often enlist independent governance advisors to explore longer-term issues like board dynamics, the board’s interface with management, and the performance of the board chair .

Third-party facilitators are frequently involved at some stage – whether to gather confidential input, benchmark practices, or provide an objective perspective on sensitive matters. In short, Canadian boards pair annual internal reviews with occasional external reviews, reflecting a balanced approach that has become standard in that market.

Europe (Continental Europe)

Across Europe, the prevalence of external board evaluations has grown significantly as corporate governance codes in many countries encourage their use. In fact, most European corporate governance codes recommend annual board performance evaluations, with many specifying that an external evaluation should be conducted at least every two to three years .

This is reflected in practice: recent data show that French companies lead in using outside facilitators (about 60% of large French companies had an externally facilitated board review in 2023), followed by the UK (41%) and Italy (38%) .

Other markets show similar patterns. In Spain, boards are legally required to evaluate the board and committees annually , and the Spanish code recommends developing an action plan to address any gaps identified . In countries like Belgium, Finland, and Luxembourg, the codes stop short of mandating a frequency for external reviews but endorse external facilitation as a best practice .

Overall, the European trend is toward greater use of independent board evaluators, aligning with the principle (promoted by the European Commission) that ongoing board evaluation enhances continuous governance improvement . Many European boards have followed these guidelines, making external reviews every few years a common fixture .

However, adoption can vary by country and company size – for example, one study found some mid-sized Swiss companies still do not disclose conducting any evaluations , indicating room for improvement in certain pockets.

Nonetheless, the trajectory in Europe is clearly toward more rigorous and regular board evaluations, with external assessments increasingly viewed as standard practice for leading companies.

7 Best Practices and Methodologies in External Board Evaluations

External board evaluations are most effective when they follow a structured process and employ a mix of quantitative and qualitative techniques. Best-practice methodologies typically include:

1. Clear Objectives and Scope:

At the outset, the board (often led by the Chair or governance committee) should define what the evaluation will cover and its goals. Common focus areas include board composition and diversity, the board’s strategic oversight, quality of discussions, decision-making processes, committee effectiveness, and individual director contributions .

Setting specific objectives ensures the review addresses relevant issues (e.g. succession planning, board culture, or a recent governance failure) .

2. Confidential Surveys/Questionnaires:

An initial step is often an anonymous questionnaire to gather candid feedback from directors (and sometimes senior executives who interact with the board). These surveys cover multiple dimensions of board performance and usually include scaled ratings as well as open-ended questions.

A key benefit of written questionnaires is that they allow anonymity, encouraging honesty . The data can be aggregated to identify trends and areas of agreement or divergence. Many boards use a consistent survey year to year to track progress, while adding custom questions to address current priorities.

3. One-on-One Interviews:

Qualitative interviews add depth to the survey data. A skilled interviewer – either the external evaluator or a board leader (like the independent chair or lead director) – meets individually with each board member to discuss perceptions of the board’s strengths and weaknesses .

These interviews probe the reasons behind survey responses and allow directors to raise sensitive issues they might not put in writing. External facilitators often conduct these interviews to preserve confidentiality; directors tend to be more forthcoming with an independent person .

Interviews may also be extended to the CEO, other C-suite executives, or even external stakeholders (investors, auditors) to gather 360-degree feedback on the board.

4. Observation and Document Review

In some external evaluations, the reviewer will observe a board meeting (or several) to see the board’s dynamics and processes in action .

They also review board materials – charters, policies, recent agendas, minutes, and board papers – to assess the quality of information flow and governance structures .

This contextual review helps evaluators judge whether the board’s practices (e.g. how agendas are set, how decisions are recorded) align with governance best practices.

5. Analysis and Benchmarking:

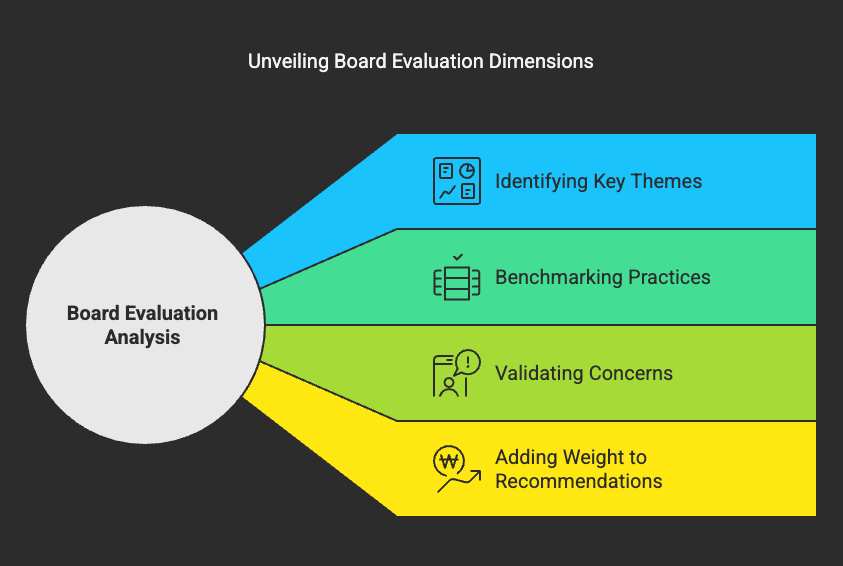

The evaluator analyzes the inputs (survey results, interview insights, observations) to identify key themes. Effective analysis will highlight both areas where the board is performing well and areas for improvement.

External reviewers often bring a benchmarking perspective, comparing the board’s practices and composition against peer companies or established guidelines.

For example, they might compare the board’s skill matrix or diversity to industry norms, or benchmark the board’s time allocation (strategic vs. operational topics) against best practice. This external perspective can validate concerns and add weight to recommendations.

6. Feedback Report and Discussion:

The findings are typically compiled into a board evaluation report that outlines the board’s strengths, weaknesses, and actionable recommendations. The report should be frank but constructive, focusing on how the board can improve its effectiveness.

Common report components include an assessment of the board’s composition and skill gaps, the effectiveness of governance processes, the quality of boardroom relationships and culture, and performance of the Chair and committees .

Best practice is for the evaluator to present the findings in a discussion with the full board, facilitating an honest dialogue among directors about the results . This plenary discussion helps ensure everyone understands the feedback and is committed to addressing it. (Often, the board will first discuss the feedback in a closed session to allow full candor.)

7. Action Plans and Follow-Up:

A crucial hallmark of a high-quality evaluation is that it doesn’t end with a report – it leads to concrete follow-up actions. Boards should develop an action plan to respond to the evaluation’s recommendations . This might include changes to board processes (e.g. meeting agendas or information provided), steps to adjust board composition (such as recruiting new directors with needed skills or not renominating underperforming directors), or additional training and development for board members.

Board leadership (the Chair or governance committee) should monitor implementation of these actions and report on progress over subsequent meetings . Many boards schedule a check-in on the action plan mid-year, and then the next annual evaluation will measure progress.

Ensuring follow-through is key to realizing the benefits of the evaluation; as governance experts emphasize, an evaluation should “culminate in specific actionable items for board improvement” to be truly effective .

In executing these steps, confidentiality and trust are paramount. Directors must feel their individual comments will not be attributed in a harmful way. External facilitators act as neutral intermediaries who anonymize feedback and create a safe space for openness.

It is also considered best practice to evaluate not just the board as a whole, but committees and individual directors (at least periodically). Leading boards perform individual peer evaluations so that each director receives feedback on their contribution .

For example, nearly half of S&P 500 boards now disclose doing some form of individual director evaluation (self or peer), a figure that is rising . Such peer review, if handled respectfully and confidentially, can help address performance issues and drive personal development for directors.

Finally, boards should tailor the methodology to their circumstances – one size does not fit all. A smaller company’s board might opt for a simpler questionnaire and brief discussion, whereas a large complex organization may need a comprehensive review with extensive interviews and benchmarks.

The evaluator should be independent and experienced, with a clear understanding of boardroom dynamics. Choosing the right external reviewer is important – boards often look for someone with credibility (e.g. a former senior director or governance expert) and ensure they have no conflicts of interest with management . When done well, an external evaluation “can help provide real insights into how a board operates and how directors work with one another,” yielding actionable takeaways that improve governance .

The better Way to evaluate boards

Gain valuable insights to strengthen your board and make better decisions.

Regulatory Requirements and Frameworks

United Kingdom

In the UK, external board evaluations are reinforced by the UK Corporate Governance Code, which operates on a “comply or explain” basis for listed companies. The Code calls for a “formal and rigorous annual evaluation” of the performance of the board, its committees, and individual directors. For FTSE 350 companies, it further recommends an externally facilitated board evaluation at least every three years . This has effectively made external reviews a de facto requirement for large UK companies.

According to Spencer Stuart data, virtually all FTSE 350 boards comply, with 99% conducting annual evaluations and nearly half using an external facilitator in the past year .

Chairs of smaller companies are also encouraged to consider periodic external reviews, and many have voluntarily adopted them. In line with the Code, the board Chair is generally responsible for ensuring that an evaluation (internal or external) is carried out and for acting on its results . Notably, the Chair’s role description explicitly includes commissioning regular external board performance reviews .

Regulators in the UK have not mandated external evaluations by law, but there is increasing focus on their quality. In recent years, the Financial Reporting Council (FRC) and industry bodies have worked to improve standards for external board reviewers.

A voluntary Code of Practice for board evaluators was introduced to bring greater transparency to how reviews are conducted and the qualifications of reviewers . This came after findings that the market for board evaluations had little quality control, leading to inconsistent approaches . The new code (developed by the Chartered Governance Institute with support from the FRC) encourages disclosure of methodology and credentials of external facilitators, though it stops short of prescribing specific methods.

Additionally, UK regulators have hinted at stronger measures if necessary to ensure external evaluations are effective. Overall, the UK framework strongly endorses external board evaluations as a pillar of good governance and has mechanisms (through the Code and investor expectations) that virtually require large companies to use them regularly.

The trend is toward even broader application (potentially all listed companies every 3 years) and higher standards for how these evaluations are done.

United States

In the U.S., there is no federal law or SEC rule that mandates board evaluations, but stock exchange listing rules and investor expectations fill the gap. The New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) requires that NYSE-listed companies’ boards (and their key audit committees, compensation, and nominating/governance) conduct a self-evaluation at least annually .

This requirement, established after the Sarbanes-Oxley reforms, does not dictate how the evaluation should be done – boards have flexibility in design – but it does ensure a yearly process is in place . The NASDAQ exchange does not have a similar explicit rule, yet many NASDAQ-listed companies also perform annual board assessments due to governance best practices and pressure from investors and proxy advisors.

Beyond the exchanges, proxy advisory firms (like ISS and Glass Lewis) and institutional investors strongly encourage regular board evaluations. For instance, BlackRock’s proxy voting guidelines encourage boards to disclose their evaluation process, including whether an external third party was used .

There is a growing sentiment among U.S. governance circles that occasional external reviews, while not required, are a mark of robust governance. Some state laws or regulations in specific sectors add additional nuances – for example, banking regulators may scrutinize board effectiveness as part of their oversight of financial institutions, effectively forcing those boards to evaluate and improve governance.

Overall, however, the U.S. relies on a comply-or-market-pressure approach: annual self-evaluations are expected (under NYSE rules) and boards are free to use external facilitators at their discretion. The flexibility in the U.S. framework means practices can vary widely, but the clear trend (under pressure from investors) is toward more transparency and rigor in the evaluation process.

Canada

Canada does not impose hard requirements for board evaluations through its laws or stock exchange rules, but it provides guidance that has made evaluations commonplace. The Canadian Securities Administrators (CSA) publish corporate governance guidelines (NP 58-201) which recommend that boards regularly assess their own effectiveness as well as that of board committees and individual directors.

Companies listed on the Toronto Stock Exchange must disclose their governance practices against these guidelines (on a comply-or-explain basis), which effectively pressures boards to conduct evaluations to avoid negative perceptions. Indeed, even without a legal mandate, regular board evaluations are regarded as best practice in Canada and have been readily adopted .

The vast majority of large Canadian companies voluntarily perform annual board and committee assessments, as evidenced by surveys and disclosures. In many proxy circulars, Canadian companies describe their board evaluation process (frequency, format, etc.), indicating how ingrained the practice has become.

Regulatory guidance in Canada is principles-based. For example, the CSA guidelines suggest that boards institute a process to assess the performance of the board, committees, and each director, and to consider the mix of skills and other qualities on the board.

There is no specification of using external evaluators – it is left to boards to decide the manner of evaluation. However, Canadian boards often look to global best practices (especially the UK and U.S.) and investor expectations. Institutional investors in Canada (and governance advocacy groups) support periodic external reviews for important boards, even if not mandated. In summary, Canada’s framework relies on guidance and disclosure: companies are expected to do board evaluations and say how they do them.

This soft approach has been effective – by 2017 it was noted that while “not legislated, regular board evaluations are recognized as a best practice” and widely in use .

As a result, Canada achieves high evaluation participation without prescriptive rules, and boards have the freedom to incorporate external facilitation as they see fit.

Europe

Across Europe, the governance landscape for board evaluations is shaped by a combination of EU-level recommendations and individual national codes. The European Commission’s 2005 recommendation on the role of non-executive directors advised that boards of listed companies should evaluate their performance annually . This set a tone that was echoed in virtually all national corporate governance codes in Europe: all major European codes call for regular (usually annual) board evaluations .

Many countries have adopted provisions in their codes or even in law to reinforce this. For example, Spain’s Companies Act requires an annual evaluation of the board, its committees, and the CEO’s performance, for listed firms .

In Italy, France, the Netherlands, and others, the codes strongly recommend annual assessments. Germany has been a bit of an outlier historically – the German Code recommends periodic self-assessment but is less specific on frequency, and German companies have been slower to embrace formal evaluations, though this is gradually changing.

When it comes to external evaluations, several European codes explicitly recommend them at set intervals. As noted earlier, the UK, France, and Spain’s codes call for an external evaluation at least every three years.

In France, the AFEP-MEDEF Code suggests that the evaluation be externally facilitated periodically (the latest guidance is at least once every three years for large companies). In Spain, while annual evaluation is required by law, using an external consultant every three years or so is encouraged to add objectivity.

Other countries take a slightly softer approach: Belgium, Finland, and Luxembourg recommend the use of external board reviewers as a best practice, but without a mandated interval . The trend is clearly toward more frequent external reviews. A comparative study by the European Corporate Governance Institute noted that in all countries examined (except Germany), the corporate governance code specified a frequency for board evaluations – ranging from annually to every 2–3 years .

European regulators and investor communities are also increasing scrutiny of board evaluation disclosure. Many national codes require that the annual corporate governance statement include information on whether a board evaluation took place that year and in some cases whether it was external.

For instance, the UK and France require companies to report when the last external evaluation occurred and if the evaluator has any connection to the company (to ensure independence). In the Netherlands, the code says the supervisory board should discuss its own functioning annually and that an external evaluator be used at least once every three years.

The EU Shareholder Rights Directive (2017) indirectly supports board evaluations by requiring large companies to explain their governance practices to shareholders, which would include board evaluation processes.

Overall, Europe’s regulatory framework on board evaluations can be summarized as: evaluate regularly, explain what you did, and periodically get an outside check. There is a high degree of conformity across countries on the importance of the practice , with some variations in how strongly external facilitation is urged.

The presence of legal requirements in some jurisdictions (e.g. Spain’s law, or the requirement in Italy for banks to evaluate their boards) indicates that where voluntary codes have not fully driven adoption, lawmakers are willing to step in. But in most of Europe, the comply-or-explain code provisions have sufficed to embed board evaluations, with external reviews becoming a governance norm at least for larger companies.

6 Challenges and Pitfalls in External Board Evaluations

When not done thoughtfully, board evaluations – even externally facilitated ones – can fall short of their potential. It’s important to be aware of common challenges and pitfalls that can undermine the effectiveness of the evaluation process.

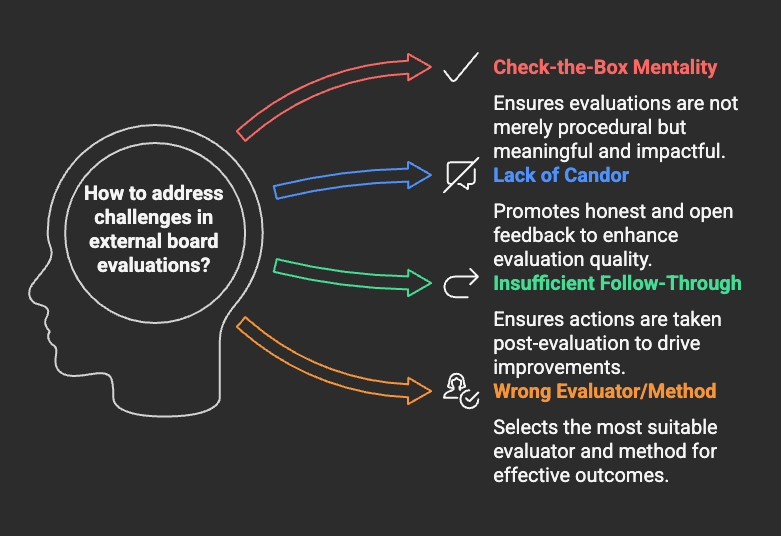

1. Check-the-Box” Mentality

A major pitfall is treating the evaluation as a perfunctory exercise to satisfy a requirement, rather than a genuine opportunity to improve. If directors are not invested in the process, the feedback will be superficial. In one survey, 44% of directors said board assessments fail to be effective because board members aren’t sufficiently invested in the process .

This can happen if the culture is one of compliance (“we have to do this”) instead of learning (“we want to get better”). Boards must approach evaluations with an open mind and a willingness to critique themselves; otherwise, it becomes a wasted ritual.

2. Lack of Candor and Honest Feedback

By nature, evaluating peers and one’s own performance is uncomfortable. Without the right facilitation, directors may hold back on giving frank feedback about sensitive issues (such as a domineering board member or a skills gap in the board).

Especially in internally led evaluations, self-criticism is likely to be muted – as one commentary quipped, those who “mark their own homework are likely to award high grades” . Even with an external evaluator, if trust isn’t established, directors might give politically correct answers.

This pitfall results in an overly rosy evaluation that overlooks real problems. Ensuring confidentiality and using techniques like anonymous surveys or private interviews with a neutral third party can help draw out more honesty. It’s also crucial for the board’s leadership to set the tone that candid, even tough, feedback is welcome and that the board has a growth mindset.

3. Insufficient Follow-Through

An evaluation has little value if its recommendations are ignored. One study found that while 74% of directors believed board evaluations enhance performance, only 58% of directors reported that their boards actually made changes in response to the last evaluation .

This “evaluation inertia” is a common pitfall – boards go through the motions of reviewing themselves, but then do not implement any meaningful improvements. Reasons can include discomfort with confronting an underperforming director, or simply inertia and other priorities crowding out follow-up.

To avoid this, boards should explicitly dedicate time to discuss the evaluation results and agree on specific actions. Assigning ownership (e.g. the nominating committee to oversee a governance improvement plan) and revisiting progress periodically can combat the tendency to shelf the report.

As governance experts note, effective boards “use the information to identify an action plan” and have board leadership monitor its execution.

4. Choosing the Wrong Evaluator or Method

Not all external evaluations are equal. A pitfall for boards new to external reviews is hiring a facilitator who lacks the requisite experience or objectivity. An inexperienced evaluator may produce a generic report with little insight, or may fail to manage group dynamics properly in interviews.

The process could then be dismissed by directors as a pointless formality. It’s “extremely important that any external facilitator… be highly experienced,” one guide warns . Boards should vet external reviewers – looking at their background, references, and approach – to ensure they can handle a board of the company’s complexity and will deliver value. Additionally, the techniques used should fit the board.

For example, a lengthy evaluation questionnaire might be overkill for a small board and lead to questionnaire fatigue, whereas a too-informal discussion might not surface deeper issues on a large board. Using a mix of methods, as discussed in Best Practices, helps avoid methodological pitfalls (each method has pros and cons).

The better Way to evaluate boards

Gain valuable insights to strengthen your board and make better decisions.

5. Groupthink or Defensive Attitudes

Sometimes boards struggle to accept criticism. If the board has a strong sense of collegiality (which is normally positive), it can turn into a barrier where directors are unwilling to single out a peer’s poor performance or to admit that the board is not functioning optimally. In such cases, evaluations may gloss over problems (“everything is fine” syndrome).

Directors might also become defensive if they feel the evaluation threatens their reputation. Overcoming this requires setting ground rules that the evaluation is about learning, not blaming, and perhaps focusing feedback on the board collectively at first rather than personalizing it.

Having an external facilitator can help break through groupthink by bringing an outsider’s viewpoint and by assuring anonymity for individual comments.

6. Confidentiality and Trust Issues

If board members fear that their individual comments or survey responses will be attributed or leaked, they will hold back. A pitfall is failing to create a truly safe environment for feedback. For instance, if the CEO or an insider runs the evaluation, other directors might worry about voicing concerns about management.

Or if one director dominates the process, others may self-censor. That’s why neutral third-party involvement is valuable – external advisors can create a more comfortable atmosphere that fosters openness and honesty.

It’s important that the board clarify that the evaluation is confidential and results will be reported in aggregate, without attributing quotes. Sometimes even within a board, comments about a peer are better collected one-on-one by the facilitator and then summarized, rather than said face-to-face in a group setting, to avoid personal friction.

In recognizing these pitfalls, boards can take steps to avoid them. This includes ensuring genuine commitment from all members, selecting a capable facilitator, guaranteeing confidentiality, and most importantly, being willing to act on the findings.

When an evaluation identifies issues – whether it’s the need for more financial expertise on the board, dysfunctional meeting dynamics, or an ineffective committee – the board should treat it as an opportunity to improve, not an embarrassment to hide.

As one prominent chair noted, “the impact of any board review depends as much – if not more – on the attitude of the board as it does on the ability of the reviewer.” In other words, a board that is open to self-improvement will gain far more from the process and avoid these common traps.

7 Future Trends and Innovations in Board Evaluation

Looking ahead, board evaluations – and the way they are conducted – are poised to evolve further. Several emerging trends and innovative practices are likely to shape external board evaluations in the UK, North America, and Europe in the coming years:

1. More Frequent and Integrated Evaluations

Boards are moving toward viewing evaluations not as an annual “event” but as part of a continuous improvement mindset. We can expect more boards to supplement the big yearly (or triennial external) review with lighter-touch check-ins.

For example, some boards now do a short evaluation at the end of each board meeting (a few quick feedback questions) to gauge meeting effectiveness and address issues in real time. This doesn’t replace the annual evaluation but makes the process more continuous.

Likewise, instead of waiting three years for an external review, some boards may bring in an external facilitator for a mini-review or targeted workshop on a specific topic (e.g. improving board/management interaction) in between full evaluations. The overall trend is that evaluation is becoming an ongoing process embedded in board culture, rather than a once-a-year checklist item.

2. Expanded Use of External Facilitators

All signs point to external board evaluations becoming even more common. Investor pressure and governance codes are increasingly favoring outside facilitation as a best practice. In the U.S., we have seen an upward tick in third-party facilitation (28% of big boards in 2024, as noted, and likely more unreported).

In Europe, countries that were slower are catching up, and the UK is contemplating requiring externals for a wider range of companies. We anticipate a future where it will be standard for boards of most significant companies to have an external evaluation at least every 2–3 years, if not more often.

Even smaller and nonprofit boards are starting to use independent reviewers as governance expectations rise across sectors (it’s already considered good practice in charities and public bodies in the UK, for instance). This wider adoption will also likely fuel a more global market of board reviewers with specialized expertise in various industries and regions.

3. Professionalization and Standards for Evaluators

With more demand for external reviews, there is a push to professionalize the field of board evaluators. We can expect the development of accreditation systems and standards for independent board reviewers. The UK’s introduction of an evaluator Code of Practice is a prime example , and international bodies like ICGN (International Corporate Governance Network) are also promoting guidelines for board review providers.

Future board evaluations might be conducted by certified professionals who adhere to an agreed set of principles (ensuring, for example, confidentiality, objectivity, and a robust methodology). This will give boards and stakeholders greater confidence in the quality of external evaluations.

It may also lead to more consistency – while each review is tailored, stakeholders might expect certain elements (like an action-oriented report and disclosure of whether an external review was done) as standard. In essence, doing an external evaluation will become not just a check of governance, but a sign that the board engaged a qualified independent advisor in line with recognized best practices.

4. Deeper Focus on Board Dynamics, Culture, and Composition

The scope of board evaluations is broadening. Traditionally, evaluations focused on processes and compliance (meeting frequency, agendas, committee structure, etc.). Future evaluations are increasingly about strategic value-add and behavioral dynamics.

For instance, boards are keen to assess “soft” aspects like: Is the board’s culture one that encourages diverse views? Are discussions collegial yet challenging? Does the board spend enough time on forward-looking strategy vs. backward-looking reporting? These questions are harder to measure but crucial to board effectiveness.

External evaluators are developing new tools – like behavioral interviews or surveys that measure psychological safety and inclusion in the boardroom – to tackle these topics. There’s also more attention on board composition and refreshment as an outcome of evaluations. With investors pushing for board refreshment, evaluations are used to identify skill gaps or underperforming directors. We might see innovations like skills matrix analytics or third-party assessments of individual directors’ contributions feeding into nomination decisions.

In fact, one trend is boards doing peer evaluations that inform succession planning – e.g. using the results to decide when to rotate a director off or what profiles to seek in new directors . Future evaluations will likely tie even more directly into board succession and recruitment efforts, ensuring the board’s composition remains fit for the company’s evolving strategy.

5. Use of Technology and Data Analytics

Technological innovation is entering the board evaluation space. We can expect digital platforms for board evaluations to become commonplace – secure tools that administer questionnaires, aggregate results in real-time dashboards, and even use analytics to highlight outlier opinions or year-over-year trends.

Some governance software providers already offer board evaluation modules that make it easier for directors to input feedback anonymously via their devices, and for the evaluator to slice the data by tenure, gender, committee, etc., to find patterns. In the future, advanced analytics or AI might play a role in analyzing qualitative comments from directors to detect sentiment or recurring themes (for example, using natural language processing on open-ended responses).

While human judgment will remain key, these tools could augment an evaluator’s ability to pinpoint issues. Additionally, as boards grapple with oversight of new areas like ESG and digital risks, evaluations might include data-driven benchmarks – e.g. comparing how much agenda time Company X’s board spends on cybersecurity vs. peers, or a network analysis of inter-director communication.

Technology could also allow for more continuous feedback loops – directors potentially being able to log feedback or suggestions through the year on a confidential portal, which the evaluator can review during the formal assessment.

6. Greater Transparency and Stakeholder Involvement

We may see a shift toward modestly more transparency about the board evaluation process and outcomes (while still keeping details confidential). Investors are increasingly asking companies to disclose the substance of their board evaluation practices, such as the general findings and improvements made.

In some European countries, codes already ask boards to confirm in the annual report that an evaluation took place and to highlight any material actions resulting. In the future, stakeholders (especially large investors) might expect boards to communicate “We had an external evaluation this year and as a result we are implementing X and Y changes.”

Such transparency can demonstrate accountability. Additionally, there is a nascent idea of involving stakeholders in board evaluations – not by revealing internal critiques, but by soliciting input from management or others about the board’s effectiveness.

A few boards have started asking the senior management team to give anonymous feedback on the board (e.g. is the board providing adequate strategic guidance? Are their interactions with management constructive?).

This 360-degree aspect could grow, especially in assessing how well the board works with management and whether it adds value. External evaluators might facilitate this by interviewing key executives or external auditors as part of the review.

7. Innovative Evaluation Techniques

Future board evaluations might borrow techniques from other fields to gain insight. For example, scenario-based evaluations or “simulations” could be used – the board might be walked through a hypothetical crisis scenario by an external facilitator to observe how the board would respond, then use that as a basis to evaluate teamwork and decision-making under stress.

This can reveal dynamics that a standard questionnaire wouldn’t. Another innovation could be psychometric assessments for boards – analyzing collective decision styles, risk appetite, or behavioral profiles of the board to see if they align with the company’s needs.

Some advisors already offer assessments of boardroom culture using organizational psychology tools. As the importance of topics like diversity and inclusion at the board level grows, evaluations may also measure those aspects (for instance, do all directors feel equally heard?

Is there any bias in how the board operates?). In sum, the toolbox for board evaluations is expanding beyond surveys and interviews to more creative methods that can uncover deeper insights and drive meaningful change.

Conclusion

In conclusion, external board evaluations are evolving from a good-governance formality to a dynamic instrument of board development. Boards and evaluators are innovating to make the process more insightful, efficient, and aligned with long-term strategy.

The focus is shifting toward using evaluations to future-proof the board – ensuring the board’s composition, culture, and processes keep pace with the fast-changing landscape of risks and stakeholder expectations.

A board that embraces these trends – by regularly inviting objective external perspectives, staying agile in its evaluation methods, and acting decisively on feedback – will be well positioned to lead its organization effectively and responsibly into the future.

Sources: External board evaluation statistics and practices are drawn from governance surveys and expert analyses, including Spencer Stuart Board Index reports , PwC’s Annual Corporate Directors Survey , the UK Corporate Governance Code and guidance , Chartered Governance Institute materials , and various corporate governance forums . These provide a foundation of data and best practices to support the insights above.