External board evaluations – independent assessments of a board’s performance conducted by outside experts – are gaining traction as a key corporate governance practice in the Philippines. With the evolving role of corporate boards from mere compliance overseers to strategic advisors, the need for regular performance reviews has intensified .

In the Philippine context, regulatory bodies and governance advocates are encouraging companies to go beyond internal self-assessments and embrace third-party evaluations to enhance board effectiveness.

This report examines the importance of external board evaluations in the Philippines, current trends and data on their adoption, methodologies and best practices in the local market, relevant regulations (including SEC guidelines), as well as the challenges, gaps, and opportunities in the board evaluation landscape.

The analysis also considers recent developments – such as Governance@Work’s partnership with Ubqty – and provides recommendations to improve board evaluation practices for Philippine boards and governance professionals.

The Importance of External Board Evaluations

Elevating Board Effectiveness

Board evaluations are now recognized as a “valuable development tool” that can drive continuous improvement in how boards function . Regular assessments help directors reflect on their performance as a group and individually, ensuring they understand their roles and responsibilities.

An effective evaluation process aligns the board’s composition and dynamics with the company’s strategy, enabling the board to provide greater strategic value and oversight. Research notes that periodic board reviews should “go beyond compliance” and aim to build high-performing boards capable of navigating emerging challenges .

In practice, this means using evaluations to identify skills gaps, improve boardroom communication, and fine-tune the board’s strategic contribution.

Objectivity and Fresh Insights

Engaging an external facilitator introduces impartiality and fresh perspectives that internal evaluations may lack. While internal self-assessments are useful, boards may struggle to be fully candid or objective when evaluating themselves.

Independent evaluators – whether consulting firms, institutes, or governance experts – can probe sensitive issues, benchmark the board’s practices against peers, and draw out more honest feedback. The Philippine Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) explicitly notes that using “an external facilitator in the assessment process increases the objectivity” of board evaluations .

This objectivity can surface blind spots and lead to more substantive improvements in governance. Ultimately, external evaluations help ensure that even well-established boards do not become complacent and continue to uphold high standards of accountability and performance.

Investor Confidence and Stakeholder Trust

In an environment where investors and stakeholders increasingly scrutinize corporate governance, robust board evaluations signal a commitment to transparency and improvement. External evaluations in particular can reassure shareholders that the board is proactively reviewing its effectiveness with independent oversight.

The Philippines’ Revised Corporation Code (2019) even expects companies to report on board performance at shareholders’ meetings . Meeting such expectations through a credible evaluation process can bolster investor confidence.

Moreover, disclosing the “criteria, process and collective results” of board assessments (as recommended by regulators) enables shareholders to see that directors are holding themselves accountable . In sum, external board evaluations serve as a governance enhancement tool – strengthening board effectiveness internally while demonstrating accountability externally.

Current Trends and Data on Board Evaluations in the Philippines

1. Growing Adoption, but Uneven Compliance

Philippine companies are gradually adopting board performance evaluations, spurred by both regulatory pressure and rising governance awareness.

A few years ago, board assessments were not universal – a 2016 survey found that while 63% of respondents conducted board self-assessments at least annually, the remaining 37% had no regular evaluation at all .

At that time, a full 75% of Philippine companies had never undergone any third-party (external) board evaluation . This indicated that external evaluations were largely uncharted territory for most boards.

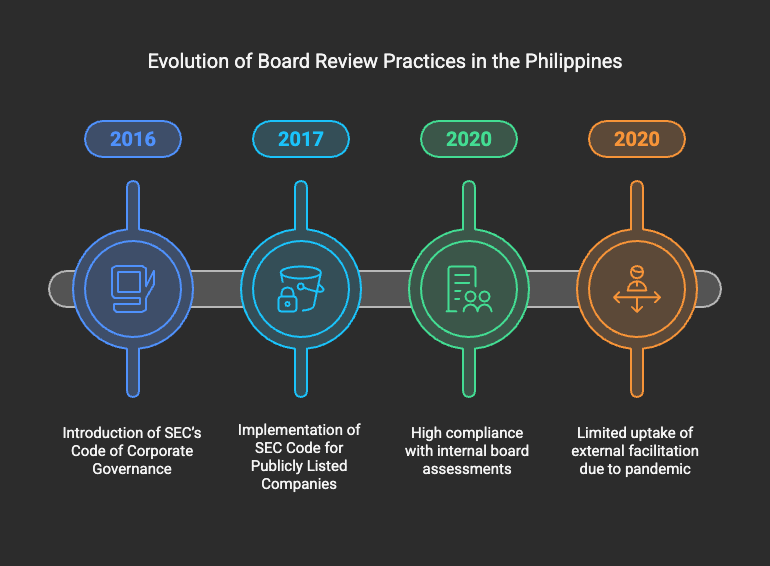

Since then, the introduction of the SEC’s 2016 Code of Corporate Governance for publicly listed companies (effective 2017) has pushed more firms to implement annual board reviews. By 2020, compliance with internal board assessments had become high among major listed firms.

A study of Philippine listed banks and holding companies showed that virtually all sampled banks (100%) and a majority of large holding firms conducted their required annual board self-evaluations .

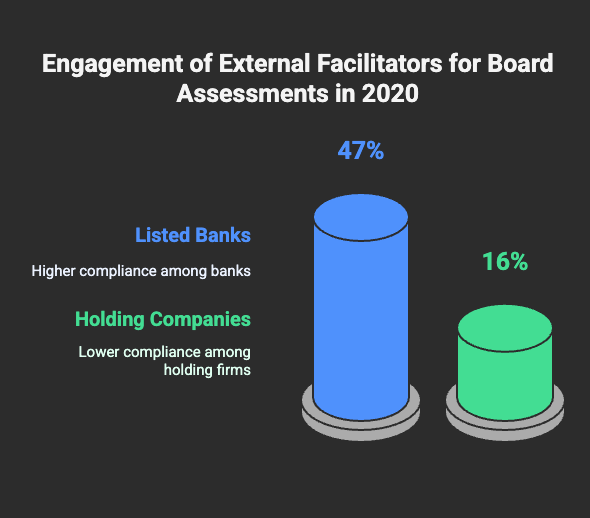

However, the uptake of external facilitation remained limited. In 2020 – the first year when engaging an independent evaluator became due under the 3-year cycle – many companies failed to comply, partly due to pandemic disruptions .

Only 7 of 15 listed banks (47%) and 6 of 37 holding companies (16%) had engaged an external facilitator for their board assessment that year . Smaller listed firms lagged behind larger ones in this regard, likely reflecting resource constraints and lesser regulatory scrutiny on smaller entities.

2. Recent Developments

As companies adjust to the new governance code and pandemic delays recede, there are signs of increasing third-party evaluation activity. Several prominent Philippine companies have voluntarily sought independent board reviews.

For example, Globe Telecom reported that in accordance with its governance policies, it engages an external evaluator every three years – in 2022 it appointed Aon Hewitt Pte. Ltd. to facilitate its board assessment, supplementing the annual self-assessment process .

Likewise, Meralco (Manila Electric Co.) disclosed that it engaged the Good Governance Advocates and Practitioners of the Philippines (GGAPP) as an external facilitator to assess the effectiveness of its board evaluation process . Some conglomerates (e.g. House of Investments, Inc.) have also enlisted third-party governance organizations like GGAPP to conduct their board evaluations, according to annual reports.

These examples reflect a growing trend of market leaders embracing external board reviews, which may encourage others to follow. Nonetheless, across the broader market, external board evaluation in the Philippines is still in early stages.

As of the early 2020s, most Philippine boards fulfill the basic requirement of annual self-review, but only a minority have institutionalized a recurring independent evaluation. This presents a significant opportunity for improvement and greater adoption of best practices in the coming years.

3 Methodologies and Best Practices in the Philippine Market

1. Internal Self-Assessments – Surveys as a Starting Point

The common approach to board evaluation in the Philippines has been an annual self-assessment using standardized questionnaires. Many companies use a survey-style assessment (often Likert-scale ratings) covering various aspects of board performance – e.g. effectiveness of board committees, quality of discussions, directors’ preparedness, and fulfillment of duties .

For instance, Globe Telecom’s board uses a comprehensive questionnaire that evaluates the board as a whole, each board committee, individual directors, the Chairman, and even management’s performance with the board . Such questionnaires are aligned with the company’s bylaws and governance charters, ensuring that the evaluation criteria map to the board’s stated responsibilities .

The self-assessment is typically coordinated by the Corporate Governance or Compliance Officer, maintaining internal confidentiality . This method allows boards to reflect on performance regularly and identify areas for improvement in a structured manner.

Best practices for self-evaluations in the local market include making the criteria transparent (some firms publish their board evaluation questionnaires on the company website for transparency) and using the findings to set priorities for the next year .

2. Use of External Facilitators – Interviews and Deeper Reviews

When boards engage an external evaluator, the methodology usually becomes more in-depth and interactive. A typical external board evaluation in the Philippines involves a combination of surveys and one-on-one interviews with directors and key executives.

For example, Bank of the Philippine Islands (BPI) and other leading banks that have undergone external board reviews enlisted independent consultants who conducted confidential interviews to supplement the survey results . Interviews enable a deeper probe into board dynamics, decision-making processes, and sensitive issues that a written questionnaire might not fully capture.

Philippine best practice is to have an experienced facilitator (often a governance consultant or institute) conduct structured interviews with each board member and possibly senior management or board advisors, to gather candid feedback in a safe setting .

The external evaluator then synthesizes the findings into a report that highlights the board’s strengths, areas for improvement, and actionable recommendations.

Notably, top Philippine companies’ external evaluation processes mirror global standards. BDO Unibank, for instance, has been cited as having a robust board evaluation practice: it used an external facilitator and combined survey questionnaires with in-depth interviews; the process solicited input not only from directors but also from senior management and external board advisors to obtain 360-degree feedback .

The evaluation covered strategic governance topics (like risk oversight) and culminated in a report of results that was presented to the full board and even creatively disclosed in the annual report.

This approach exemplifies best practice methodology – independent and thorough, yet tailored to the company’s context.

3. Focus on Development and Action Plans

Whether internal or external, the most effective board evaluations in the Philippines focus on developmental outcomes rather than just scoring performance.

A well-designed evaluation process leads to concrete follow-ups: boards develop action plans to address weaknesses (for example, scheduling additional training where knowledge gaps are identified, or adjusting board agendas and information flow if meeting effectiveness was a concern).

The SEC’s guidance stresses that evaluation results should be “shared, discussed” by the board and that “concrete action plans” be implemented to improve identified areas . Many companies channel evaluation insights into their director training and succession planning.

It is considered a good practice for the board (often via the Corporate Governance Committee) to formally review the evaluation feedback and then endorse specific governance enhancements – such as revising board policies, updating committee charters, or mentoring underperforming directors.

In summary, Philippine boards that derive real value from evaluations are those that treat it as a continuous improvement cycle: performing a thorough assessment, openly discussing results, and committing to measurable steps for strengthening governance year over year.

Regulatory Framework and SEC Guidelines

SEC Code of Corporate Governance (2016): The Securities and Exchange Commission of the Philippines introduced explicit board evaluation requirements in its Code of Corporate Governance for Publicly Listed Companies (SEC Memorandum Circular No. 19, s.2016).

This Code established Principle 6: Board Performance Assessment, under which Recommendation 6.1 mandates that “The Board should conduct an annual self-assessment of its performance, including the performance of the Chairman, individual members and committees.” It further specifies that “Every three years, the assessment should be supported by an external facilitator.”

In practice, this means all publicly listed firms are expected to have yearly board evaluations, and at least once in three years, an independent third party should be engaged to assist with the review. The Code’s Recommendation 6.2 requires companies to have a system for board evaluation with defined criteria and process, and ideally a feedback mechanism for shareholders .

While the Code stops short of mandating public disclosure of board evaluation results, its Explanation notes that disclosure of the “criteria, process and collective results of the assessment” can help shareholders judge the board’s performance .

In contrast to neighboring countries’ codes, the Philippine code does not strictly require announcing evaluation details in the annual report, but companies are encouraged to be transparent.

These SEC guidelines took effect January 2017, and companies were given time to comply with the new practices. The first cycle for mandatory external facilitation came due in 2020. As discussed, not all companies met this immediately (with some citing COVID-19 disruptions), but compliance has been improving.

The SEC monitors adherence to these provisions through the Integrated Annual Corporate Governance Report (I-ACGR) that listed firms must submit. The I-ACGR includes sections where companies report whether and how they conducted board evaluations and if an external facilitator was used, making it a disclosure-based enforcement mechanism.

Beyond listed companies, the SEC code has been influential in setting expectations for good governance across the corporate sector. For example, banks and insurance companies have parallel governance guidelines (from the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas and Insurance Commission) which also emphasize board performance assessments, aligning with SEC’s standards for publicly listed entities.

Other Governance Frameworks: The Revised Corporation Code of 2019 indirectly supports board evaluations by requiring certain disclosures to shareholders. Specifically, Section 49 of the code provides that at annual stockholders’ meetings, the board should endeavor to present “appraisals and performance reports for the board and the criteria and procedures for assessment.”

While this doesn’t mandate a formal evaluation, it implies that companies should have some systematic assessment of board performance to report to their owners. Additionally, the Philippines participates in the ASEAN Corporate Governance Scorecard (ACGS) program, which benchmarks listed companies’ governance practices against regional best practices.

Under the ACGS criteria, having a formal board assessment and disclosing its conduct can earn companies points towards their governance score . This has provided an extra incentive for leading companies to adopt not just the letter but the spirit of board evaluation practices to achieve recognition (e.g. the “ASEAN Golden Arrow” awards for top governance scorers).

Lastly, professional bodies like the Institute of Corporate Directors (ICD) and GGAPP have been actively promoting evaluation practices through director training and offering assessment services. These organizations complement the regulatory framework by spreading best-practice methodologies and, in some cases, acting as external evaluators themselves.

4 Challenges and Gaps in Current Board Evaluation Practices

1. Compliance vs. Effectiveness

A key challenge observed in the Philippines is ensuring that board evaluations are meaningful exercises rather than perfunctory, “for compliance only” activities . Since the SEC made annual evaluations a checkbox item, many boards dutifully comply but may treat it as a formality.

Studies have found that some Philippine boards conduct evaluations to satisfy regulations or contexts (the lowest level of accountability), with directors having “little knowledge about the purpose behind the exercise.”

If the mindset is merely to fill out a form once a year, the process can devolve into a mechanical routine that fails to drive improvement. High reported compliance rates therefore do not always translate to more effective boards. Indeed, the “high-performing boards” the code envisions will only materialize if evaluations are used as a tool for genuine reflection and change.

Bridging the gap between compliance and effectiveness remains a challenge – one that requires shifting boardroom culture to openly embrace feedback and development.

2. Resource and Capability Constraints

Another gap is the disparity between large and small companies in implementing robust evaluations. Philippine regulators noted that board assessment “requires time, commitment, and resources,” which has meant that primarily the larger corporations have fully complied .

Smaller publicly listed firms, family-owned companies, and organizations with limited budgets face challenges in conducting comprehensive evaluations or hiring external consultants. They may lack in-house expertise to design good evaluation surveys or the funds to pay for third-party facilitators.

Moreover, there is a limited pool of experienced external evaluators in the local market. While consulting firms (including the Big Four), ICD, and GGAPP offer board assessment services, this practice is still nascent.

The academic review of listed firms in 2020 observed “there may be no shortage of external facilitators, [but] regulators and companies must be aware that the type and independence of the external facilitator can affect the quality of board evaluation” .

In other words, as demand grows, ensuring evaluators are truly qualified and unbiased is a concern. Currently, there is no formal accreditation or standard for board evaluators in the Philippines, making it challenging for boards to identify credible providers.

This gap could potentially undermine confidence in external assessments if not addressed (e.g. a poorly executed review by an unqualified third party might create confusion or mistrust).

3. Cultural Reluctance and Sensitivities

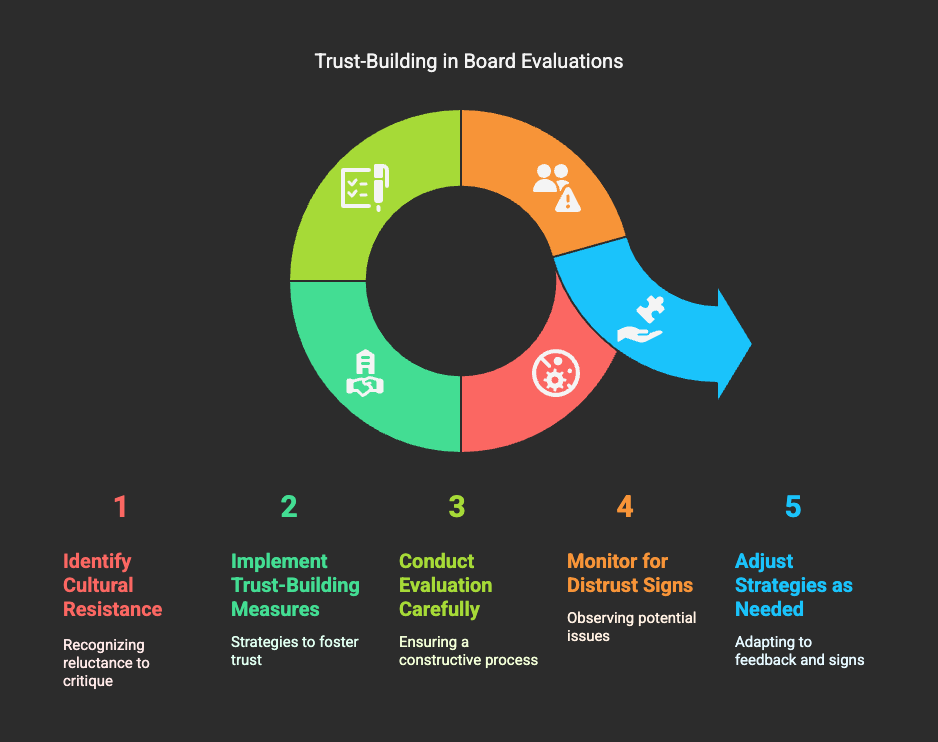

Board evaluations – especially those involving peer review or external scrutiny – can be sensitive. Philippine boards often operate in close-knit circles (with many directors having longstanding professional or personal ties), and introducing critical evaluations can be uncomfortable.

Some directors may be hesitant to be frank in self-assessments for fear of offending colleagues or creating conflict. Similarly, boards might be wary of airing any “dirty laundry” to an outsider facilitator, worrying about confidentiality.

The challenge is to overcome the cultural resistance to critique and to build trust in the process. If not handled well, an evaluation can even “lead to distrust among board members and between the board and management, eroding board cohesiveness”.

Thus, one gap lies in capability-building: boards need guidance on how to conduct evaluations constructively – e.g. setting ground rules for anonymity, focusing on behaviors not personalities, and framing the exercise as developmental, not punitive. Only with the right facilitation and mindset can boards feel safe to engage in candid performance discussions.

4. Disclosure and Follow-through

Finally, there is a gap in how results are used and communicated. While the SEC recommends disclosing the fact that a board evaluation took place and high-level results, many companies provide minimal information to shareholders. Some firms simply state that a board assessment was done, without detailing findings or improvement steps – often out of concern that negative findings could be used against them.

In 2020, most Philippine companies did not publicly share detailed outcomes of their board reviews, with transparency largely limited to noting compliance . Without transparency, however, shareholders and stakeholders cannot gauge whether the board is truly improving.

Additionally, not all boards rigorously follow through on evaluation findings. In some cases, issues identified recur year after year in evaluations because no concrete action was taken.

This lack of systematic follow-through undermines the value of the exercise. Ensuring that evaluations lead to visible governance enhancements (and reporting back on those changes) is an area needing improvement.

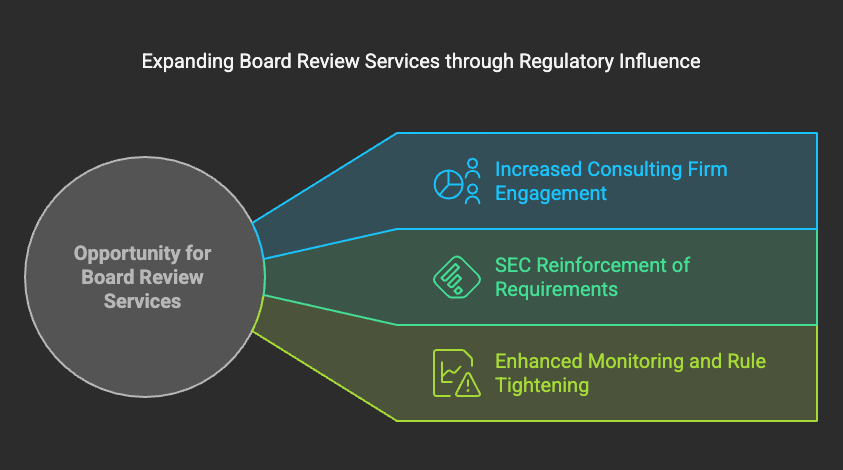

4 Opportunities for External Board Evaluations

Despite the challenges, the current landscape presents significant opportunities to enhance and expand external board evaluations in the Philippines. The convergence of regulatory expectations, market pressure, and available solutions creates a timely moment to drive progress:

1. Regulatory Backing and Enforcement

The Philippine SEC’s clear guidance provides a strong foundation to build upon. As companies internalize the requirement of an external evaluation every three years, the demand for independent facilitators is set to increase.

This opens the door for more consulting firms and governance institutes to offer specialized board review services. There is an opportunity for the SEC and governance advocates to reinforce this requirement through more explicit monitoring and perhaps tightening the rules (e.g. making disclosure of whether an external review was done in a given year a required statement in annual reports).

Strong regulatory backing can normalize external evaluations as a standard practice by default rather than the exception. In time, failing to have a periodic external board review could be seen as a red flag for investors, which incentivizes companies to comply not just in form but in substance.

2. Governance@Work and Ubqty Partnership

The entrance of international players and new technologies into the Philippine governance scene is a major opportunity. Governance@Work, a Sweden-based leader in digital board evaluation platforms, recently formed a strategic partnership with UBQTY Inc. (a Philippine consulting firm) to bring “cutting-edge governance tools and services to Southeast Asia.”

This collaboration is poised to “deliver tailored governance solutions” that combine global best-practice frameworks with local insight .

For Filipino boards, this means access to advanced SaaS-based board evaluation tools – for example, secure online survey platforms, benchmarking analytics, and automated reporting dashboards – that can greatly simplify and enrich the evaluation process.

The partnership effectively makes digital external board evaluations more accessible and affordable to Philippine companies, including those that may not have engaged external reviewers before.

By leveraging such technology, boards can conduct thorough assessments with guidance from global experts, all while respecting “cultural norms” and regional governance nuances .

The timing is opportune: as boards adapt to more virtual and data-driven ways of working (accelerated by the pandemic), a digital evaluation platform can slot naturally into their workflow.

Governance@Work’s entry, via Ubqty, also stimulates competition and innovation in the local board advisory market – prompting existing providers to up their game and offering boards more choices for external evaluation services.

3. Capacity Building and Professional Services

There is an opportunity to develop a cadre of accredited board evaluation experts within the Philippines. As noted in academic research, the “establishment of accreditation criteria for external facilitators” may become essential as more boards seek third-party reviews . P

rofessional bodies (ICD, GGAPP, etc.), possibly in collaboration with the SEC or academic institutions, could create certification programs for board evaluators. This would ensure a common standard of quality and ethics, making companies more comfortable in engaging external help.

It also opens up a niche consulting field – governance professionals (retired executives, experienced directors, consultants) can be trained to serve as independent board reviewers. For consulting and law firms, helping boards conduct evaluations is a value-added service that complements other governance offerings (e.g. corporate secretarial or audit services).

In short, as awareness grows, a market for external board evaluation is emerging. Both local and international service providers have the opportunity to support Philippine companies in this area, whether through bespoke consulting engagements, peer benchmarking services, or software solutions.

4. Enhanced Board Performance and Competitiveness

Ultimately, companies that seize these opportunities stand to gain a competitive advantage through superior governance. External board evaluations, when properly utilized, can lead to better decision-making, more cohesive boards, and improved oversight – all of which contribute to long-term corporate success.

With Filipino conglomerates expanding regionally and seeking international investors, demonstrating world-class board practices is a plus.

Boards that proactively undergo independent evaluations signal their commitment to excellence, potentially attracting higher valuations and lower cost of capital (as good governance often correlates with investor confidence).

Moreover, as environmental, social, and governance (ESG) criteria take center stage, robust board evaluation processes will be viewed as part of the “G” in ESG metrics.

Companies have an opportunity to integrate their board assessment with broader governance improvements, such as board diversity initiatives and strategy retreats, thereby future-proofing their leadership.

In essence, those who embrace external evaluations early can position themselves as governance leaders in the Philippines and the ASEAN region.

6 Recommendations for Improving Board Evaluation Practices

To address the challenges and capitalize on the opportunities, Philippine boards and regulators can take several practical steps to strengthen external board evaluation practices:

1. Foster a Learning Culture on Boards

Directors and executives should be oriented that board evaluations are a developmental tool rather than a compliance drill. Building awareness is crucial – regulators, institutes, and even Chairman of boards should emphasize the true objective of evaluations (to improve board effectiveness).

As one study highlighted, creating “correct awareness among regulators, companies, directors, and other stakeholders on the proper objective, design, and execution” of board evaluations is key to getting meaningful results .

Boards could incorporate a brief educational session or facilitator’s briefing before each evaluation to remind participants of the purpose and benefits. By framing the exercise positively (as an opportunity to sharpen the board’s saw), directors are more likely to engage honestly and constructively.

2. Strengthen Regulatory Guidance and Enforcement

The SEC can consider enhancing the framework for board evaluations.

This could include issuing guidelines or best practice bulletins on how to conduct effective assessments (covering use of external facilitators, suggested evaluation criteria, etc.), drawn from global standards.

Over time, the SEC might require companies to disclose in their annual reports or I-ACGR not just whether an evaluation was done, but also when the last external evaluation took place and a high-level summary of actions taken as a result.

Clearer disclosure requirements would nudge companies to actually implement recommendations from evaluations. Additionally, as suggested by experts, regulators in collaboration with professional bodies could develop an accreditation system for external board evaluators .

Having a list of accredited evaluators or a certification program would assure companies of quality and encourage more boards to seek outside help with confidence.

3. Leverage Technology and Expert Partnerships

Companies should take advantage of new digital tools and services now available for board evaluations. Platforms from providers like Governance@Work (through its local partner Ubqty) can streamline the process, offering user-friendly survey interfaces, data analytics, and even anonymity features that encourage frank feedback.

Boards are advised to pilot these modern solutions, which often come with built-in best practice questionnaires and reporting formats. Engaging a tech-enabled external facilitator can also reduce costs compared to purely bespoke consulting, making it feasible for mid-sized firms to get third-party input.

Furthermore, Philippine companies could consider peer learning opportunities – for instance, joining roundtables or forums (perhaps organized by ICD or GGAPP) where boards that have done external evaluations share their experiences. Learning from peers can demystify the process and highlight practical do’s and don’ts for methodology.

4. Ensure Comprehensive and Candid Evaluations

For each evaluation cycle, whether internal or external, boards should aim for a thorough review of all key dimensions of performance.

This means evaluating not just compliance metrics, but also qualitative aspects like boardroom dynamics, the quality of strategic guidance, risk governance, and the board’s relationship with management.

Incorporating one-on-one interviews or focus group discussions in addition to surveys is highly recommended to gather richer insights .

Boards might also implement director peer reviews (each director is assessed by fellow board members) in a confidential manner to foster individual accountability. To encourage candor, companies can utilize independent facilitators or anonymous response tools even for internal assessments.

Clarity of questions is important – templates or sample questionnaires from credible sources (e.g. Diligent, IFC, OECD) can be adapted to the Philippine context. By designing the evaluation to be comprehensive and safe for honest input, boards can better diagnose their performance issues.

5. Translate Results into Action Plans

Perhaps the most critical recommendation is to close the loop after the evaluation. Every board evaluation should result in a written action plan or set of next steps approved by the board.

The Corporate Governance Committee (or equivalent) can be tasked to track progress on these improvement items over the subsequent year.

Action plans might include specific initiatives such as: scheduling a board strategy workshop, adjusting meeting schedules or materials, recruiting a new director with needed expertise, providing training on emerging topics (e.g. digital transformation, ESG), or updating company policies.

The SEC already expects boards to “develop and implement concrete action plans” based on evaluation findings – boards should treat this as a mandatory follow-up.

Moreover, communicating the changes to stakeholders is a good practice. For instance, the next annual shareholders’ meeting or annual report could mention, “Based on the board’s 2023 evaluation, the board undertook the following governance enhancements…”

Such transparency demonstrates that the evaluation is not a paper exercise but a catalyst for continuous improvement.

6. Periodic External Reviews and Continuous Improvement

Boards should institutionalize the practice of engaging an external evaluator at least every 3 years, if not more often for those that desire annual external feedback.

The choice of external facilitator should be considered carefully – look for independence, experience in corporate governance, and a strong track record . Even academic institutions or seasoned directors from institutes can serve this role, as allowed by SEC (the facilitator can be “any independent third party such as, but not limited to, a consulting firm, academic institution or professional organization” ).

Once engaged, the board should treat the external review as an opportunity to benchmark itself against global best practices and identify aspirational goals.

Philippine boards might also consider alternating facilitators over time to gain different perspectives. Finally, continuous improvement means learning from each evaluation cycle – issues identified in one cycle should ideally not recur, because the board addresses them. Over multiple cycles, the board’s governance maturity should visibly improve.

Companies can even integrate board evaluation findings into their board renewal and succession planning – for example, using the insights on skill gaps or director performance to inform which new directors to recruit or what leadership development to pursue for current members .

By implementing these recommendations, Philippine companies can derive far greater value from board evaluations and ensure that the practice fulfills its promise of stronger governance. An external board evaluation should evolve from being seen as an obligation to being embraced as a strategic investment in the company’s leadership and long-term success.

Conclusion

External board evaluations in the Philippines are at an inflection point. They have moved from a novel concept to a recognized best practice underpinned by SEC regulations and growing market acceptance.

While initial compliance has been encouraging – especially among top-tier companies – the true potential of board evaluations to elevate governance standards is yet to be fully realized. The trends and data indicate that many boards still have room to deepen the rigor and authenticity of their assessments, and to incorporate independent perspectives more regularly.

Fortunately, the ecosystem to support this is strengthening: regulatory frameworks are aligning with international norms, new partnerships (like Governance@Work and Ubqty) are bringing in innovation, and local governance organizations are championing better practices.

For board professionals, members, and advisors in the Philippines, the message is clear: embrace external board evaluations as a tool for excellence.

By doing so, boards can unlock candid insights into their effectiveness, address governance gaps proactively, and ultimately drive higher performance for their organizations.

As one governance survey noted, a “thorough and robust Board assessment process” should guide boards in reassessing their composition, competencies, and priorities, and then “subsequently, the Board should take action on the results of these assessments.”

In essence, it is not the evaluation itself, but the improvements that follow, that deliver value. The opportunity now is for Philippine boards to turn these evaluations into a cornerstone of their governance culture – making continuous improvement in the boardroom a norm.

With committed leadership and the practical steps outlined above, external board evaluations can significantly contribute to enhanced corporate governance and sustained business success in the Philippines.